Here's the crazy thing: I worked for 23 stations in 20 years. I've heard of people who worked at more stations, but I haven't met anyone who did.

Half of the time during this period, I worked part-time, mostly in the earlier years while attending high school and college, and then again in the later years while working full time for a consulting engineering company and a publishing company. Sometimes I worked for more than one station at a time, such as a period when I worked for KIMN and KUAD; KWBZ and KLAK; and KPPL and KDKO. That was somewhat unusual in the business, but somehow it worked out.

This employment record includes more than 23 individual jobs, though, because I was hired several times at the same stations, sometimes after returning from out-of-state college terms, sometimes after having quit to go to another station, and sometimes after having been terminated.

Work in broadcasting often has been referred to as a "revolving door" because many on-air employees move station-to-station in rapid succession. That was certainly was my experience.

Here is a fairly accurate resume of my broadcasting career, followed by some recollections of my time at various stations in no particular order.

| Don Bishop broadcasting resume | | | |

In Boulder, Colorado, a somewhat older next-door neighbor boy, Leslie Hazzard, once told me about a rock 'n' roll radio station he had been listening to. A Denver station, KIMN, was playing the Top 40 records. I was age 8, too young for the music to appeal to me, but by fifth grade, I was listening. Transistor radios were new, and 1960s students had to have them the way today's students must have cell phones with short messaging service, musical ring tones and built-in cameras. I depleted many 9-volt batteries by falling asleep at night while listening to KIMN on a transistor radio through my pillow to circumvent my mother's ban on nighttime listening.

Many cities and towns had a dominant Top 40 station that most teenagers listened to, and in the Denver area, that station was KIMN. Parents and teachers mostly hated it. That they were annoyed by it only contributed to its appeal to students and young adults.

My junior high classmate Steve Armstrong and I used a wire recorder—yes, a wire recorder—to emulate disk jockeys and hear ourselves on playback.

By age 16, I wanted to be a deejay. My father helped me to make appointments with managers at several Denver radio stations. He wanted me to learn more about what a deejay job involved. If he hoped that would dissuade me, he never let on.

At KOSI, I spoke with the general manager, Bob Kindred. Andres Neidig received me at Spanish-language KFSC. I arrived for my appointment at KIMN to find that the station's owner/manager, Ken Palmer, had passed the task of speaking with me to the program director, Jack Merker. KIMN occupied a somewhat battered-looking studio near Sloan Lake in Edgewater, a few blocks west of the Denver city limit.

My visits to these stations reinforced my desire to work as a deejay and, in particular, to one day work at KIMN.

In high school, I participated in the weekly half-hour high school radio program that speech teacher Wally Schneider arranged to broadcast on KBOL, the Boulder radio station owned by Russ Schafer.

Later on, at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, I hosted weekend programs on what then was a 650-watt student-run radio station, KCSU-FM. When I applied for the job, I brought an audition tape, thanks to some time spent in the KBOL production studio. The student program director, Ted Scott, said that he normally gave newsreading assignments to freshmen. But because I was the only one ever to bring an audition tape (and to wear a suit to the job interview), he started me with a 7-hour deejay shift on Saturday evenings.

Within three months, Mike Meisel, the operations director of KCOL, then a Fort Collins station on 1410 AM, called me during a shift at KCSU-FM and offered me a job. I began work as a KCOL deejay from 7–11 p.m., Sunday through Friday. I later filled in on the morning show when its host, Ed Nesselroad, was away on six months' national guard duty.

Scott graduated from CSU and took a job as program director for KUAD, then a new daytime station on 1170 AM in Windsor, Colorado that played country-and-western music in a rotation similar to Top 40. KUAD was licensed to H.P. Brewer and managed by his son, Phil Brewer.

Scott called me and offered me more money to leave KCOL for KUAD. Yes, more money. After one year, KCOL had given me a raise from $1.60/hr to $1.70/hr (I had asked for a 25-cent raise.) Ted offered $2.25/hr. For that princely sum, yes, I could go country.

So there I was, in 1970, on my third radio job while going to college, and two of the jobs had come looking for me. What a good line of work to be in, I was thinking. I set about to polish my Top 40-like delivery with KUAD's country music.

In April 1971, I awoke in my dormitory room to hear new voices on KIMN from the clock radio. The station had changed hands. Pacific and Southern Broadcasting, the new owner, swept out all the deejays except one full-timer, Bill Stevens (Dave Shaw), and one part-timer, R.T. Simpson. Gone were the familiar voices of Jay Mack (James MacIsaac), Ross Reagan (Ross Jay) and Danny Davis. (Davis actually had been terminated by the outgoing owner shortly before the ownership change; otherwise, the incoming owner had planned to retain him.) News Director Don Martin was let go the same day, followed the next day by Assistant News Director Tony Lamonica. Morning news anchor Phil Mueller was elevated to news director before being let go a few weeks later. In April 1971, I awoke in my dormitory room to hear new voices on KIMN from the clock radio. The station had changed hands. Pacific and Southern Broadcasting, the new owner, swept out all the deejays except one full-timer, Bill Stevens (Dave Shaw), and one part-timer, R.T. Simpson. Gone were the familiar voices of Jay Mack (James MacIsaac), Ross Reagan (Ross Jay) and Danny Davis. (Davis actually had been terminated by the outgoing owner shortly before the ownership change; otherwise, the incoming owner had planned to retain him.) News Director Don Martin was let go the same day, followed the next day by Assistant News Director Tony Lamonica. Morning news anchor Phil Mueller was elevated to news director before being let go a few weeks later.

Brandt Miller took the morning slot, followed by Stevens, who had been moved out of mornings. Stevens had been reassigned to a two-hour, late-morning slot and production duties. Jon Reed was noon to 4; Randy Robins 4 to 8; and Michael Collins 8 to midnight. Part-timer R.T. Simpson was heard midnight to 6. Brandt Miller took the morning slot, followed by Stevens, who had been moved out of mornings. Stevens had been reassigned to a two-hour, late-morning slot and production duties. Jon Reed was noon to 4; Randy Robins 4 to 8; and Michael Collins 8 to midnight. Part-timer R.T. Simpson was heard midnight to 6.

Granted, all the changes had been made. But I got on the phone to KIMN's program director, Walt Turner, anyway. Did he have room for one more? Me? Turner said to come and see him the next day, and bring an audition tape.

I made a tape that evening using the KUAD control room after the daytimer signed off: Top 40 music with KUAD's country jingles. Turner listened to the tape at 10 the next morning, and he wasn't enthusiastic about what he heard.

"You need some work," he said, and my heart fell. "Can you start tomorrow?" he asked, and my flat heart pumped up again.

The problem was, one of the deejays Turner had hired failed to arrive. Turner was one deejay short, and that's why Simpson, a Denver University student, was working the overnight shift. Another deejay whom Turner had only then hired for the overnight shift, Chris Alexander (Alan Lawson), was due in two weeks. Simpson couldn't work every night and attend college, and Turner hired me "temporarily" to alternate nights with Simpson.

| So what? I was elated. There I was, five years after my visit with Jack Merker, working on KIMN. It was a dream come true, even if it was overnights and temporary. Such is the stuff that dreams are made of.

The two weeks passed; Chris Alexander arrived; and Turner added another part-timer, Al Jefferson (Adam Dempsey), whose work he liked better than mine. I paid Turner a visit for him to critique a recording of my program as he reviewed all the jocks' shows. He still wasn't that impressed, and I thought the temporary job was ending. |

I asked Turner whether I would be on the schedule for the following weekend, and he said, "of course." It helped that I had a First Class FCC license, which meant I could deejay and sign the transmitter log. Simpson and Jefferson had Third Class licenses, so Turner had to pay another man with a First Class license, Alan Lewis, to "babysit" the transmitter when the other two worked night or weekend shifts and the chief engineer wasn't on duty.

I worked the following year-and-a-half at KIMN before leaving Colorado for graduate school in Michigan. I had two and sometimes three shifts on the weekend, and worked overnights when a full-timer would be away due to illness or vacation. I hosted a Sunday evening talk show devised to fulfill part of the station's public affairs programming commitment. I had the time of my life working at my dream radio station.

In the mid-1970s, KIMN was faltering, and for a brief period, rival KTLK surpassed it in the ratings.

In 1974, John Edwards was working KTLK's 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. shift. He and I had worked together at the college station in Fort Collins. He suggested that I apply for a part-time position with KTLK because he and some other staffers were dissatisfied with the part-timer then working there.

The program director, Bobby Rivers (Robert Burchette), hired me and assigned me to shifts including 2–6 a.m. and 6–10 p.m. Saturday and 10 a.m.–2 p.m. Sunday. I was working Monday–Friday for the Denver office of Massachusetts Indemnity and Life Insurance Company.

I asked Rivers whether there were some projects I could help him with that would expose me to the work necessary for programming the station. As long as I offered my time for free, he said he was willing.

I started coming in to the station about twice a week around 4 p.m.; Rivers' airshift ended at 3 o'clock. The only task he gave me was to file records. I was excluded from everything else, including the weekly conference call with the programming consultant that I figured would be really interesting. After a couple of weeks' worth of filing records, I told Rivers that I wasn't learning anything in exchange for the time spent, and I stopped volunteering my time. I started coming in to the station about twice a week around 4 p.m.; Rivers' airshift ended at 3 o'clock. The only task he gave me was to file records. I was excluded from everything else, including the weekly conference call with the programming consultant that I figured would be really interesting. After a couple of weeks' worth of filing records, I told Rivers that I wasn't learning anything in exchange for the time spent, and I stopped volunteering my time.

During the summer of 1975, Rivers asked me to handle a weekday shift for two weeks while the morning deejay took vacation time. Rivers shuffled the schedule to move the regular air staff to earlier time slots and offered me the choice of the 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. or the 2–6 a.m. shift.

I chose the 10 p.m. shift for perhaps a larger audience and settled in for the two weeks. I mean, really settled in. There wasn't enough time to go home to the suburbs between my work at the insurance agency and the radio station. My car became my clothes closet, and the KTLK lobby became my bedroom. The men's room had a convenient shower stall.

When I finished the airshift at 2 a.m., I would bed down on the couch in the lobby and awaken by 6:30 a.m. to shower, put on fresh clothes and drive to the insurance agency. After nearly two weeks of this schedule, I was dead on my feet. I wrote Rivers a memo telling him I couldn't fill in on weekdays anymore, but I had to retrieve it from his office before he read it. I had found a memo from Rivers waiting for me, assigning me to another week because the afternoon deejay had decided to take vacation as soon as the morning deejay would return.

I finished the three weeks and told Rivers, "no more." He said that my decision meant that he doubted I could continue with the radio station because he had to have a part-timer available for vacation fill-in. Maybe he was being petulant or bluffing, because when I called the next Friday to ask whether I was scheduled for the weekend, he said of course I was—I was "important to the station."

The station had a slogan that I always found to be out of alignment with, well, the call letters. What I mean is that the call letters, KTLK, had two "K"s in it, but they weren't consecutive. That didn't stand in the way of the slogan, "Denver's Double K." By way of emphasis, the "K"s were printed in larger size. Maybe that's what made the difference. The station had a slogan that I always found to be out of alignment with, well, the call letters. What I mean is that the call letters, KTLK, had two "K"s in it, but they weren't consecutive. That didn't stand in the way of the slogan, "Denver's Double K." By way of emphasis, the "K"s were printed in larger size. Maybe that's what made the difference.

KTLK had two production wizards. The morning deejay, Dan Alexander (Michael Wolfgang) assembled some amazing commercials in the station's tiny production studio that doubled as a news anchor booth. Ron Lee (Ron Thompkins) could make magic with razor-blade splices, overdubbing, echo effects and his own versatile voice.

Alexander had the deepest voice at the station, so his work was featured on a lot of commercials. And the nature of his voice, along with its relative exclusivity, figured into my bumpy transition to full-time work with the station.

I wasn't making progress at the insurance agency, so when the overnight deejay left KTLK, I applied for the position. Rivers took a week or so to make up his mind, but then he told me I had the job—or so I thought. I gave notice at the insurance agency and prepared to return to full-time radio work. But then Rivers said he wasn't sure I was right for the job. He explained that the station needed another deep voice to take some of the load off of Alexander.

Surprised, I explained to Rivers that he had confirmed to me that I had the job, and on that basis I had resigned from the agency. He should follow through on his commitment, I told him. A day or two later he said he would honor his previous agreement. I don't think he was disappointed from the commercial production standpoint. I had a few tricks of my own and later developed a reputation as something of a wizard with a vocal range (with special effects assistance) that extended from bass to tenor.

The afternoon drive deejay, Robb Steele, said that he favored hiring me for the overnight show. His theory was that listeners using clock radios would be more likely to leave their radios dialed to KTLK for the morning wakeup if they liked what they heard at night when they set the alarm. I don't know whether there had been any research to indicate the truth in that, but I was pleased to have his support. The afternoon drive deejay, Robb Steele, said that he favored hiring me for the overnight show. His theory was that listeners using clock radios would be more likely to leave their radios dialed to KTLK for the morning wakeup if they liked what they heard at night when they set the alarm. I don't know whether there had been any research to indicate the truth in that, but I was pleased to have his support.

By the time I started hosting the overnight show, shifts had been extended to reduce the deejay headcount and save money. The published schedule was midnight–5 a.m.; 5–10 a.m.; 10 a.m.–3 p.m.; 3–7 p.m.; and 7 p.m.–midnight. A snowstorm struck during my first shift as a full-timer, and morning deejay Alexander arrived at 5 a.m.

But the next two mornings, he didn't arrive until 5:30. The following morning, 5:40. I had said my on-air goodbye at 5 a.m., so I segued records until Alexander came in. On that third morning, I said something to him about being late. He asked, "Didn't Rivers tell you?" I asked him what he meant, and he said that the absentee owner wouldn't pay his high salary for a four-hour shift, so he and Rivers worked out a scheme to say that his program started at 5:00. But Alexander said he would arrive anytime he pleased between 5:00 and 6:00, and I could take it or leave it.

I adjusted to the situation and continued my show past the nominal 5 a.m. ending time. I never again delivered "end of show" remarks because I never knew when my show would end for the day. Whenever Alexander arrived, he would replace me at the microphone while music was playing.

Rivers had a rule: Never play songs by black artists back-to-back. When Rivers was critiquing a recording of my program, he heard me follow a song by a black group with Donna Summer's "Love to Love You, Baby. He was angry that I had violated the rule. But I told him I didn't know Donna Summer was black. "If it sounds black, don't play it back-to-back," he replied. I said that Summer didn't sound black to me, and could the tape cartridges perhaps be labeled to indicate the artists' race? That never happened. Rivers had a rule: Never play songs by black artists back-to-back. When Rivers was critiquing a recording of my program, he heard me follow a song by a black group with Donna Summer's "Love to Love You, Baby. He was angry that I had violated the rule. But I told him I didn't know Donna Summer was black. "If it sounds black, don't play it back-to-back," he replied. I said that Summer didn't sound black to me, and could the tape cartridges perhaps be labeled to indicate the artists' race? That never happened.

As valuable as I might have been to KTLK as a part-timer, my value as a full-time deejay apparently never was demonstrated, and a few months into 1976, Rivers let me go. I soon was hired for the 7 p.m. – midnight shift at country-and-western KLAK, where I began what was my longest tenure with one radio employer, at two-and-a-half years.

I returned to KTLK in 1981. The program director I worked for at KDKO, Jim O'Brien (Jim Mullica), was friends with Ed Greene, who was KTLK's program director at that time. O'Brien's recommendation carried enough weight that Greene hired me immediately. He said he liked my "1960s sound," whatever that was. KTLK was sold not long after, and I made the transition to the new ownership and a change from rock 'n' roll to country-and-western with new call letters: KBRQ.

My footnote in KTLK history is that I hosted the morning show on the last day that the station played rock 'n' roll.

Pete Smythe's "General Store" morning program on Denver's KOA 850 AM was popular in the 1950s and 1960s, and he hosted an afternoon program by the same name on KOA-TV Channel 4 from 1954 to 1969. It's my opinion that Smythe was more-or-less forced into retirement when KOA later redirected its programming from a rural appeal supported by its 50,000-watt signal to focus instead on the Denver metro audience. Smythe would banter with Elmy Elrod and Moat Watkins, characters that he voiced. His hayseed program was funny, but the broadcast from the pretend rural location of East Tincup, Colorado on the "Bob Wire Network" didn't fit as KOA pursued a city audience.

Ken Lange, a Denver radio station executive, and Pete Smythe bought KADX-RM in the 1970s when FM stations were't pricey and FM audiences were small. Smythe was installed as the morning show host. On KADX, he replicated the program he previously broadcast on KOA. Unfortunately, the signal could not reach Smythe's former, loyal, rural audience. Metro-area listeners either didn't know he was back on the air after an absence of several years, or mostly didn't care. Smythe soon left the morning show, becoming a silent partner as Lange changed KADX into a jazz station. "My Irish investment," he called it. The reference meant that Lange would call him each month to tell him how big a check he had to write as his part of making up the station's cash operating shortfall. Ken Lange, a Denver radio station executive, and Pete Smythe bought KADX-RM in the 1970s when FM stations were't pricey and FM audiences were small. Smythe was installed as the morning show host. On KADX, he replicated the program he previously broadcast on KOA. Unfortunately, the signal could not reach Smythe's former, loyal, rural audience. Metro-area listeners either didn't know he was back on the air after an absence of several years, or mostly didn't care. Smythe soon left the morning show, becoming a silent partner as Lange changed KADX into a jazz station. "My Irish investment," he called it. The reference meant that Lange would call him each month to tell him how big a check he had to write as his part of making up the station's cash operating shortfall.

Beginning in 1971 and continuing for 28 years, Smythe was seen on TV and in newspapers and heard on radio when he became the advertising spokesman for a Denver savings and loan association, First Federal Savings. He died in 2000. Continuing into the 21st century, his recorded voice still could be heard on the public address announcements at Denver International Airport, warning airport shuttle riders about door openings and closings and the starts and stops of shuttle motion. It makes me smile to hear his voice there.

KADX had one of the weaker FM signals in Denver because its tower was near the intersection of Hampden Ave. and Peoria Ave. in southeast Denver. Although that is relatively high ground, Denver's other FM stations used antennas on mountaintop sites to the west of the city. The weak signal further limited the station's value.

In 1981, Smythe and his partner were happy to accept a $3.1 million purchase offer from Great Empire Broadcasting. They made up their operating losses and exited with a profit.

To consolidate their two Denver stations, Great Empire abandoned the KADX studio in the building at the tower base and built a new one at 1265 S. Delaware Ave. That was the studio location of its KBRQ 1280 AM station that played country-and-western music. Great Empire officials publicly stated an intention to keep the jazz format, even though the company's other nine properties played country. Jazz remained at KADX for the following seven months, until the station was reconstituted as "105 Country" (KBRQ-FM).

I was working at KBRQ-AM when KADX was purchased and moved into the Delaware location. I remember that some of the AM station staffers were envious as the KADX studio was built because its fresh construction meant a cleaner, modern look and better equipment compared to the aging AM studio.

The jazz station deejays didn't mix much with the country station deejays, and I remember only Dennis Papin, the evening deejay, and Steve Burke, the morning deejay. My interaction came about in part because one of my tasks as a weekend deejay and news anchor on the AM station was to record news for broadcast on KADX.

As is common, the newscast ended with a weather forecast. I wanted to do something different to be entertaining on KADX, and I came up with the idea of writing the forecast as though the news boadcast were emanating from a rare wood-paneled studio decorated with tapestries and paintings by the masters or from a remote studio fitted into a classic car.

I interlaced the weather statistics with a rambling, descriptive narrative that would place Papin, for example, in a Rolls Royce Silver Shadow as he broadcast. He liked it, and I would leave him typed copies of a normal forecast and the embellished one. Those pieces of paper would survive the night, and Burke said he enjoyed the creative writing, too. The KADX program director, whose name I don't remember, sought me out and said she liked the innovation.

My weekend work at the co-located KADX-KBRQ studio facilities allowed me to visit with John Dunning, who hosted a segment of old time radio programs Sundays on KADX. Dunning's program bounced from station to station over a period of a couple of decades. Perhaps the only time Dunning's program benefited from the audio clarity of FM was when he broadcast on KADX. My weekend work at the co-located KADX-KBRQ studio facilities allowed me to visit with John Dunning, who hosted a segment of old time radio programs Sundays on KADX. Dunning's program bounced from station to station over a period of a couple of decades. Perhaps the only time Dunning's program benefited from the audio clarity of FM was when he broadcast on KADX.

I became an old-time radio enthusiast. Until I left Denver at the end of 1986, I would listen to Dunning's program wherever it was broadcast. These days, old-time radio programs are readily available via streaming audio on the Internet and on inexpensive CDs containing nearly 100 programs each in MP3 compressed audio files.

The station where I probably had the most fun and got in the most trouble—and maybe the two aspects are related—was KBRQ. Let's get right to the trouble.

I had been working part-time at KBRQ 1280 AM for a year-and-a-half leading up to October 1982, when I said something on the air that was in poor taste. As a result, Skip Schmidt, the general manager, terminated me.

The program director, Roger Mundy (Terry Frazier), said that Schmidt had not thought highly of me. "You handed him an excuse," Munday said, explaining that maybe some discipline was in order, but that he didn't think termination was necessary.

Halloween was approaching, and a week or two before, seven people had died of poisoning in the Chicago area from ingesting Tylenol laced with cyanide. That notorious case of product tampering led to today's use of seals on food and drug containers, and the more widespread use of tablets instead of more easily contaminated capsules. Halloween was approaching, and a week or two before, seven people had died of poisoning in the Chicago area from ingesting Tylenol laced with cyanide. That notorious case of product tampering led to today's use of seals on food and drug containers, and the more widespread use of tablets instead of more easily contaminated capsules.

What had I said? I suggested on the air that a scary thing to do for Halloween would be to hand out Tylenol. It wasn't one of my better ad-libs.

A listener sent Schmidt a complaint letter. Schmidt spoke to Mundy. Mundy called me at the consulting engineering firm where I worked full time as the general manager. He asked me what I had said, and I repeated my remarks as I remembered them.

Mundy asked me to come in to the station, where he told me I was terminated. Schmidt wouldn't see me that day, but he accepted an appointment for me to come in and talk with him the following week. He told me at that time that he thought I had no bad intentions, but that he didn't have confidence in me.

Previous to my errant remark, Mundy told me that Schmidt had observed me eating a meal in the studio on a Sunday and wanted Mundy to ask me not to. I explained that on Sundays I came in at 6 a.m. to prepare parts of several newscasts, and then I worked a deejay shift from 7 a.m.–noon. During that shift, I also delivered the news at :00 and :30 and sports at :45. For that one shift, I was the only deejay who doubled up on news and deejay responsibilities through the entire broadcast week.

When my deejay shift ended at noon, I continued delivering the three elements of news per hour as a news anchor until 3:05 p.m. Then I had a three-hour break, and I went back on the air as a deejay from 6 p.m.–midnight. When, I asked Mundy, was I expected to eat if I didn't consume some food in the studio during the 15 hours I put in on Sundays? He said, "Now I understand; don't worry about it." When my deejay shift ended at noon, I continued delivering the three elements of news per hour as a news anchor until 3:05 p.m. Then I had a three-hour break, and I went back on the air as a deejay from 6 p.m.–midnight. When, I asked Mundy, was I expected to eat if I didn't consume some food in the studio during the 15 hours I put in on Sundays? He said, "Now I understand; don't worry about it."

About a year after my termination, Schmidt left the station for a job in Florida. Frank Gunn took up the GM responsibilities, and Mundy rehired me. Mundy said that my work was better than other deejays who were available to work part time, plus he liked the fact that I had other full-time work. It meant I didn't bother him with requests for a full-time job or seek offers for full-time radio work elsewhere and leave after a short time as most other part-timers—understandably—did.

Mundy first hired me in 1981 when Great Empire Broadcasting purchased rock 'n' roll KTLK 1280 AM and changed it to country-and-western KBRQ. I already worked part-time at KTLK, and I had ample experience on country stations. I don't remember much about the "job continuation" interview except that Mundy asked me whether I liked to make dates with girls who called on the request line. Only in radio, huh?

The other KTLK deejay to make the transition was the overnight man, Mark McColl, who was given the same shift on KBRQ.

I asked not to be assigned to work on Friday or Saturday evenings or to the overnight shift. I was occasionally asked to work a Friday night, especially when I was subbing Monday–Friday in the 7 p.m.–midnight slot either as a deejay or news anchor, but otherwise, Mundy honored my request. I was enjoying my day job and getting plenty of airtime on KBRQ.

Mundy hired other part-timers to work some of the other shifts, including Justin D. Fogg (think about it) and Roger Allen, whom he likened to "a big old bear who just wandered in to play records." Mundy hired other part-timers to work some of the other shifts, including Justin D. Fogg (think about it) and Roger Allen, whom he likened to "a big old bear who just wandered in to play records."

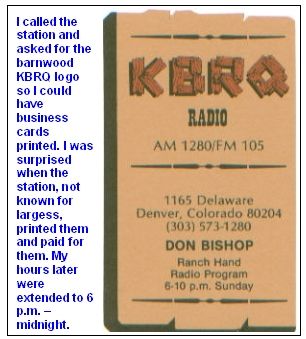

I wore a suit to my day job, so when I would take time to attend KBRQ staff meetings on weekdays, I hardly looked the part of a "ranch hand," as the KBRQ deejays were called. I called myself "Country Don" to play up the difference.

Then came the termination.

My firing had been kept quiet, as I learned after a few days. I had no opportunity to say goodbye to my fellow ranch hands and others at the station. Instead, I sent handwritten letters to the station addressed to those I knew well. When the letters arrived, I started getting phone calls at the engineering company from staffers who expressed their surprise and disappointment.

One call was from Dave Jackson, the news director. He hadn't been told of my termination. I had been anchoring the news on Saturday and Sunday. Was my termination only as a deejay, or also from the news department, he wanted to know. I told him I was willing to continue with the news. He called back to say he was told he would not be allowed to keep me on in news.

When I went to my appointment with Schmidt the next week, he told me he thought my sending letters to the staff to say goodbye "was a classy thing to do." Well, well.

During my year away from KBRQ, I didn't seek any other radio work. I accepted an offer from a publishing company to become a senior editor on two of its technical trade magazines. The work involved travel that I enjoyed, and I extended my trips over weekends so I could tour the cities where I had assignments.

When Mundy rehired me at KBRQ in 1984, I limited my weekend work to Sunday evenings. I also worked weekday fill-in as needed. Limiting my availablity on weekends meant I could continue my touring when I had an out-of-town magazine assignment and still get a return flight in time to arrive at the station for the Sunday show. As a plus, the weekend shows were simulcast on AM and FM, so I had a much larger potential audience compared to my previous stint on KBRQ when I was on the AM station only. When Mundy rehired me at KBRQ in 1984, I limited my weekend work to Sunday evenings. I also worked weekday fill-in as needed. Limiting my availablity on weekends meant I could continue my touring when I had an out-of-town magazine assignment and still get a return flight in time to arrive at the station for the Sunday show. As a plus, the weekend shows were simulcast on AM and FM, so I had a much larger potential audience compared to my previous stint on KBRQ when I was on the AM station only.

I spent many hours preparing for those Sunday shows. During the week, I wrote comedy bits for delivery between songs, and I wrote scripts for one funny phone call per hour. I would mail the scripts to a retired radio broadcaster, Tony Larson. Before the show, I would call Larson from the production studio and record the conversations for later use. He used a variety of disguised voices and imitations.

Mundy and his successor as program director, Green Daniel, didn't mind my on-air antics, which were a departure from the usual presentation. Daniel said when I arrived with my briefcase full of material, it looked as though I were doing a morning show. The new general manager, Frank Gunn, at first didn't even know what was going on during Sunday evenings. As a result, I had a free hand, but I kept in mind the Tylenol joke and didn't stray over the line.

I met Gunn when he visited the station one weekend, and I saw him in a hallway. I stepped up and introduced myself, and he asked what I did at the station. When I told him I was on the air, he said he was embarrassed not to know that.

I figured my visibility with the weekday staff was almost nil and could use some improvement. I started sending recordings of my program to Gunn, and I sent them to the commercial sales representatives, too. I would tell the sales representatives in advance about content I was planning that might have some appeal to various possible advertisers. No one ever had sold time specifically for a Sunday evening show before. And as it turned out, no one did this time, either!

One of the sales reps, Ed Brady, was intrigued by my promotional efforts. Brady also had a background as an air personality. He recognized the creative effort being expended, and occasionally he would ask for me specifically to produce commercials for his clients. To draw such a request as a part-timer really pleased me. One of the sales reps, Ed Brady, was intrigued by my promotional efforts. Brady also had a background as an air personality. He recognized the creative effort being expended, and occasionally he would ask for me specifically to produce commercials for his clients. To draw such a request as a part-timer really pleased me.

And the time came during this period when I surprised Mundy by applying for a full-time job with the station.

If I remember right—and my recollection could be fuzzy on this so I had better not name names—the morning deejay had a fistfight in the parking lot with the news director. The deejay was said to have been a drinker. He was fired. That's all I remember, except that it created a job opening.

I was happy at the publishing company, but I regretted not having had more success in broadcasting. I decided to apply for the morning deejay job.

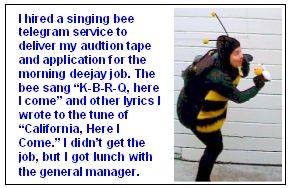

I wrote lyrics to the song, "California, Here I Come" that said "K-B-R-Q, Here I Come" and hired a singing telegram service to send someone to the station to sing it to Mundy. The "singing bee" also delivered a large box with a tiny cassette audition tape.

The result? Gunn called to invite me to lunch. There, he said he had already decided to hire Sandy Travis, but that my display of initiative deserved a free lunch. I returned the favor and invited him to lunch—at a better restaurant—a few weeks later. He may not have known I worked for the station when he first met me in the hall, but by now he did! The result? Gunn called to invite me to lunch. There, he said he had already decided to hire Sandy Travis, but that my display of initiative deserved a free lunch. I returned the favor and invited him to lunch—at a better restaurant—a few weeks later. He may not have known I worked for the station when he first met me in the hall, but by now he did!

Six months to a year later, Gunn called and asked me to meet with him and Great Empire's national program director. During the meeting, they said they were going to replace Mundy and had me in mind for the program director job. They said they were impressed with the way I was producing my Sunday show and wanted me to bring improved production values to the rest of the broadcast schedule.

Also, even though they hadn't hired me for the morning show, they said I could give myself a mid-day shift if I wanted.

It was a good offer (so it seemed; more about that to come). I gave it careful consideration. But I turned it down and told them that I really wanted the personal satisfaction of hosting a morning show. The program director job was something I would have wanted years before, but it wasn't something I would leave publishing for at that time.

The job went to Green Daniel, who also was a part-timer at the station with programming experience, and he made some production value changes. He kept me on as the Sunday evening deejay and said he likened my program to a "feature" broadcast. I didn't know what that meant, but it was positive, so I didn't question it.

In October 1986, the publishing company where I worked sold the magazines I edited to an out-of-town company, and I had to relocate. I made my last broadcast on KBRQ on Dec. 7, 1986, and that was the end of my work in radio. I had been blessed with a wonderful time during my "second chance" at KBRQ and 105 Country.

The following spring, Shamrock Broadcasting announced that it was purchasing KBRQ and 105 Country from Great Empire. When the transaction closed, all the deejays and many other employees were replaced. In what was a rare gesture in the broadcasting business, Great Empire offered to transfer displaced employees to work at the company's other stations. A number accepted the offer, including Gunn, who went to KWKH in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Someone from Shamrock later told me that Gunn and the Great Empire national program director knew the stations were to be sold when they offered me the KBRQ program director job. It was to have been a short-lived position—but I suppose I would have been offered a transfer, too.

Around 1991, Gunn called me from Shreveport to talk with me about the possibility of becoming the morning deejay there. It was tempting: morning deejay on a 50,000-watt AM station. He had remembered what I said I wanted, and he called. But I couldn't do it. I was giving care to my father who had relocated near my home; the publishing work was going well; and I still enjoyed the travel that my work offered. It wasn't the time to return to broadcasting.

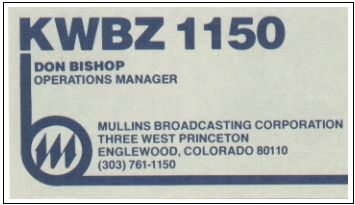

Paul Pettit, whom I had met when we worked together at KDKO, was working for a consulting engineer who had a contract to add a nighttime signal to KWBZ's daytime coverage. The project was in its final stages when Petit suggested that I apply for a job as the station's production director.

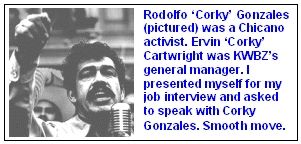

E.L. "Corky" Cartwright was the majority owner and general manager. John C. Mullins Jr., heir to the estate of the man who founded Denver's channel 9 TV station, was a minority owner.

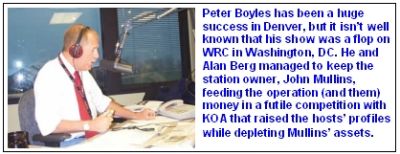

Peter Boyles was the nominal program director. At the talk station, the program hosts worked mostly independent of supervision. But Pettit suggested I call Boyles, who we both knew from our previous work at KLAK where Boyles had shared the morning show with Bob Lee.

The best time to reach Boyles, Pettit told me, was right after he finished his show. I tried several times, but he never picked up my call. I later came to understand that Boyles was a nice enough fellow to work with, but if he had nothing to gain from an association with someone, he wouldn't give them any time.

Here's a story of getting off on the wrong foot: Failing to reach Boyles, I made an appointment to see the general manager. At the scheduled time, I arrived and told the receptionist, Sjana, that I was there to see Corky Gonzales. Remember, the general manager's name was Cartwright. A man named Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales was a Chicano activist who had been in and out of trouble with the law. Here's a story of getting off on the wrong foot: Failing to reach Boyles, I made an appointment to see the general manager. At the scheduled time, I arrived and told the receptionist, Sjana, that I was there to see Corky Gonzales. Remember, the general manager's name was Cartwright. A man named Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales was a Chicano activist who had been in and out of trouble with the law.

Sjana said, "We don't have anyone here named Corky Gonzales." From the room behind her I heard someone say, "He means me, Sjana."

I walked in and said, breezily, "Nothing like making a good first impression!" Cartwright was good-natured about it, though, and said that his nickname had caused other people to mix him up with Gonzales sometimes.

Cartwright hired me to work on a part-time basis not to exceed three hours per day—and said I should record the commercials in less time, if possible. The tiny production room with huge glass windows sat opposite the talk show hosts' air studio, which itself amounted to no more than a conference table, an ancient Western Electric speakerphone and three EV 635A microphones.

If you don't know, 635As are inexpensive microphones not often found in the main studio of a station in a large market. They're tough, though, and I often saw them used for spot news and remote broadcasts and in small-market station studios.

You get the idea. KWBZ was low-budget. The production room had no headphones, and I didn't own any. I recorded my voice for playback and mixed it with music from a turntable. The station had no music licenses, so I used only a Tanner music library. The limitations posed a challenge, and the challenge made it fun, so I had a ball getting the best possible results by speeding and slowing the recorders, splicing tape and mixing music. I kept strict timing for the 30- and 60-second commercials so they could air between network news and sports. The board operators couldn't insert local spots in that position before, because previously when the talk hosts recorded the commercials, they couldn't time their spots—or wouldn't bother to. You get the idea. KWBZ was low-budget. The production room had no headphones, and I didn't own any. I recorded my voice for playback and mixed it with music from a turntable. The station had no music licenses, so I used only a Tanner music library. The limitations posed a challenge, and the challenge made it fun, so I had a ball getting the best possible results by speeding and slowing the recorders, splicing tape and mixing music. I kept strict timing for the 30- and 60-second commercials so they could air between network news and sports. The board operators couldn't insert local spots in that position before, because previously when the talk hosts recorded the commercials, they couldn't time their spots—or wouldn't bother to.

Cartwright soon contracted with a roving band of specialty commercial salesmen who used telemarketing to sell anybody and everybody a series of commercials based on a so-called safety campaign. They sold a lot, and sold 'em cheap. I would arrive to find production orders for as many as 25 spots, some that were scheduled to air only once. After three hours, I would emerge from the production room with a stack of carts a foot-and-a-half high.

Kathy Bradshaw, the morning board operator, watched me through the glass as I sped through the work and produced a volume of spots. I used the Tanner music and jingle library with as much creativity as I could muster. For the fun of it and off the clock, I produced sign-on and sign-off announcements that Boyles thought were so funny that he played them on his show. Otherwise, they played only once a week when the station signed off for maintenance Sunday night and returned to the air Monday morning.

Mullins liked my versatility. "When I was driving up to the station just now, I heard three of your commercials play in a row. If I didn't know it was your voice, I could swear they were recorded by different people," he said.

Shortly thereafter, Mullins bought out Cartwright's interest in the station, promoted me to a full-time position as operations manager, and gave me a talk show airshift of my own.

I also had impressed him with a few technical tricks. For example, when I started with the station, KWBZ had just begun to use its new nighttime signal. It was barely audible. Most people thought it was because the power was less. But that wasn't the problem. The pre-amplifiers feeding the control board output into the phone lines to the separate nighttime transmitter weren't adjusted right. I reached into the equipment rack and turned up the output adjustment. Instantly, the nighttime signal was loud enough to hear. I also had impressed him with a few technical tricks. For example, when I started with the station, KWBZ had just begun to use its new nighttime signal. It was barely audible. Most people thought it was because the power was less. But that wasn't the problem. The pre-amplifiers feeding the control board output into the phone lines to the separate nighttime transmitter weren't adjusted right. I reached into the equipment rack and turned up the output adjustment. Instantly, the nighttime signal was loud enough to hear.

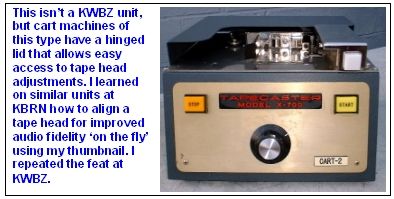

As another example, the commercials sounded muffled on the air. I lifted the lids on the cart machines and adjusted the playback head azimuth with my thumbnail. Instantly, the audio cleared up.

These were easy things to do, but no one else had thought to do them, so I looked pretty bright.

In my new position, I promoted Bradshaw from board operator to overnight talk show host. I hired someone she recommended, Sharon Katchen, for weekend talk shows. Later, the two of them covered 7 p.m. to 6 a.m., sometimes exchanging shifts. They were so reliable, I let them schedule themselves. Bradshaw later moved on to KOA. Katchen later worked at KIMN, and then moved to Los Angeles and KFWB. In my new position, I promoted Bradshaw from board operator to overnight talk show host. I hired someone she recommended, Sharon Katchen, for weekend talk shows. Later, the two of them covered 7 p.m. to 6 a.m., sometimes exchanging shifts. They were so reliable, I let them schedule themselves. Bradshaw later moved on to KOA. Katchen later worked at KIMN, and then moved to Los Angeles and KFWB.

Bradshaw once called me at home about 1:30 a.m. to say that KWBZ was off the air. When I turned on a radio, I could tell that the signal was there, but without audio. That meant a trip to the studio, not the transmitter.

When I got to the studio, I saw that the control board was off. The overnight shift was "combo," meaning Bradshaw operated the board and lined up calls during breaks and hosted her show. While swinging her feet under the console table, she had kicked the power plug out of the wall. I plugged it back in. Voila! Back on the air . . .

Another time, power to the entire studio failed during afternoon drive, probably because of lightning from a thunderstorm. At the time, KWBZ was broadcasting a remote from the Denver Bronco football team training camp in Fort Collins, Colorado, via a telephone line. The remote represented a lot of advertising dollars. Mullins asked me whether there was anything I could do. Another time, power to the entire studio failed during afternoon drive, probably because of lightning from a thunderstorm. At the time, KWBZ was broadcasting a remote from the Denver Bronco football team training camp in Fort Collins, Colorado, via a telephone line. The remote represented a lot of advertising dollars. Mullins asked me whether there was anything I could do.

I thought for a moment, and then it occurred to me that the remote came in on a telephone line. The audio from the control board went out to the transmitter on a telephone line. I plugged a patch cord into each connection, feeding the remote telephone line directly into the transmitter telephone line. Voila! Back on the air . . .

KWBZ was an affiliate of the ABC Information Network. It had also had the ABC contract to broadcast Paul Harvey's "News and Comment" and "The Rest of the Story." The station often pre-empted ABC network news to air local news except at night and on weekends. In effect, ABC was a national sales agent, because ABC paid KWBZ to air the commercials that came with the news, whether the news itself aired or not. Amazingly enough, when I became operations director, I discovered that the station wasn't playing the commercials it missed when it pre-empted ABC news (and sports, on the weekends.)

The station's business manager, Dee Thompson, showed me a stack of affidavits sent by ABC that hadn't been filled out for a couple of months. The affidavits listed every commercial that the network had fed to the station. I called ABC and learned how to use future affidavits to schedule the spots. The network had sent the spots in advance by mail on tape reels, and because no one at the station knew what they were for, they also had been set aside. I dubbed the spots to tape cartridges, scheduled the commercials on the log and thereafter filled out the affidavits and sent them to ABC for an instant reveue boost.

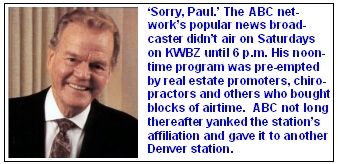

Mullins was proud of the ABC affiliation. The TV station his father had owned was an ABC affiliate. When Mullins took over KWBZ, he spoke with ABC and received the network's assurances that it would not switch to another station. KWBZ's failure to air the network's commercials couldn't have helped. Neither did the way the station scheduled the Paul Harvey's "Saturday News and Comment."

KWBZ sold program time on the weekends to all comers: chiropractors, real estate promoters (I'm thinking of the two hosts in that category who later were charged with crimes), restauranteurs, telephone system sales companies, you name it. The time was blocked out from 6 a.m.–6 p.m. on Saturday. KWBZ aired the hourly ABC news on weekends but pre-empted the sports that followed at :06. It also pre-empted the 15-minute Harvey news that was fed down the network line about 10:30 a.m. so stations could record it for broadcast around noontime.

KWBZ aired Harvey's Saturday news program at 6 p.m. As a part-timer, I thought that was odd. As operations director, I found that the delay violated the station's network contract and voided the network's obligation to pay the station for commercials aired by Harvey. I talked with the network, and the latest ABC would allow Harvey's Saturday program to air was 1 p.m. That would cut into the chiropractor's time, which had been 1:05 p.m.–2 p.m. KWBZ aired Harvey's Saturday news program at 6 p.m. As a part-timer, I thought that was odd. As operations director, I found that the delay violated the station's network contract and voided the network's obligation to pay the station for commercials aired by Harvey. I talked with the network, and the latest ABC would allow Harvey's Saturday program to air was 1 p.m. That would cut into the chiropractor's time, which had been 1:05 p.m.–2 p.m.

Mullins had mixed reactions to my ABC-related "discoveries." He wanted to do things "right," but he wasn't happy when the chiropractor—who later was charged with practicing medicine without a license when he gave patients some of the services he promoted on KWBZ—negotiated a small reduction in his program fee when Harvey was rescheduled at 1 p.m. to please ABC and qualify the station for the network's commercial payments. The real estate promoter, who later became a fugitive from justice, wouldn't permit interrupting his 11 a.m.–1 p.m. show for a Harvey newscast at noon.

It wasn't long before ABC—despite its assurances to Mullins—moved its broadcasts to another Denver station with better coverage and probably a larger audience. Correcting the commercial and Paul Harvey clearance problems may have been too little and may have come too late.

Here's another quirky twist that bothered Mullins when it came to light: The station was violating the FCC's rule that required broadcasters to charge political candidates the lowest published advertising fequency rate, regardless of the quantity of commercials they bought. Here's another quirky twist that bothered Mullins when it came to light: The station was violating the FCC's rule that required broadcasters to charge political candidates the lowest published advertising fequency rate, regardless of the quantity of commercials they bought.

KWBZ was nominally an Englewood, Colorado station, and a candidate for Englewood city council, Harry Fleenor, bought spots. Both Mullins and Fleenor were unaware of the FCC rule, so Mullins was charging Fleenor the higher rate for spots in drive time.

I looked into the billing with the business manager and called attention to the FCC rule. I may have protected the station from a possible FCC fine should Fleenor have wised up, but it didn't please Mullins. He reduced Fleenor's rate and moved the spots out of drive time. When I asked Fleenor about this in 2005, said he had paid in advance and didn't get a partial refund.

Boyles was hosting the morning show when he accepted an offer to host an overnight talk show on WRC, Washington. That move to a larger market and the national capital proved too attractive to pass up, and Boyles left for DC.

Mullins first replaced Boyles with Rex Morgan, a man with a lot of broadcasting experience that included television, but as it turned out, he was a terrible radio talk show host. He left after only a week or two.

Next, Mullins tapped Tony Larson, a longtime and highly respected radio news broadcaster. Larson crafted program wheels for each hour and prepared meticulously for his broadcasts. I don't remember much about the content, but the results didn't entirely please Mullins.

Meanwhile, Boyles was not having a successful experience at WRC, although his difficulty was not known at the time. Mullins called him and made him an offer to return to KWBZ for what might have been a large salary increase, and Boyles was only too happy to come home. Meanwhile, Boyles was not having a successful experience at WRC, although his difficulty was not known at the time. Mullins called him and made him an offer to return to KWBZ for what might have been a large salary increase, and Boyles was only too happy to come home.

Mullins also negotiated with Alan Berg to return as a talk host on the 1150 AM dial position. Berg had debuted in talk radio in 1974 prior to the Cartwright/Mullins purchase when the station was KGMC. An attorney, Berg had worked as a prosecutor in Illinois before leaving law practice and moving to Colorado for work in a tailoring shop—and Berg indeed did spend most of his money on clothes—and cars.

Berg seemed easy to anger, on and off the air. He once told me that although he was somewhat volatile by nature, he emphasized that personality aspect for the sake of his broadcasts. He was known for berating listeners, hanging up on callers and talking frankly about sex (a subject not commonly discussed on talk shows in those days). He riled up bigots who hated him for his opinions and because he was Jewish.

Mullins took me aside one day and said, "I have good news and bad news." He said the good news was that he had hired Berg, and the bad news for me was that he was taking my show off the air. Berg occupied the 10 a.m.–2 p.m. time slot, replacing my 10 a.m.–noon talk show. I continued with the rest of my responsibilities, which were plenty. Fact is, it had been difficult to give the talk show the attention it deserved.

A highlight to my talk show was this: Mullins asked me to devise the program to appeal mostly to women. I discovered that I had a talent for reading published text aloud, paraphrasing it as I did and making it sound like off-the-cuff comments. A highlight to my talk show was this: Mullins asked me to devise the program to appeal mostly to women. I discovered that I had a talent for reading published text aloud, paraphrasing it as I did and making it sound like off-the-cuff comments.

I had the most response from women callers when I started my programs with items from Cosmopolitan and the National Enquirer.

On one occasion, I was paraphrasing a Cosmo article to start the show when a caller came on the air to say, "When you first started on the station, I thought you were really stupid. But I've been listening to you for the past 15 minutes, and you really understand women, don't you?" I wish, my friend; I wish.

Berg started his job and immediately generated the buzz that Mullins wanted. The radio columnists in the newspapers liked to write about Berg, and that was valuable free publicity.

One day, Fred Wilkins, said to be the head of the local Ku Klux Klan, came in the front door, hurried past the receptionist and entered the studio when Berg was on the air. He pointed his finger at Berg and said: "I'm Fred Wilkins. You're gonna die." Then he turned and left. Berg's microphone was on, and I later listened to the words as they were captured on the logging tape.

Unsettled by the security breach (actually, there was no security), Berg left the studio and went flapping around in the lobby, venting his outrage. The board operator, Dave Dennis, called me on the intercom and said he needed help. With Berg absent from the studio, Dennis had been playing commercials and promotional announcements for several minutes.

I took my place in the studio and hosted the program until Berg settled down and returned.

Berg stated that Wilkins had pointed a gun at him. Whether he made that up to embellish his story of the incident or really believed it, I never knew. Dennis confided in me that he saw Wilkins clearly and that the man only pointed a finger. But he asked me not to say anything about it because he feared that unless he sided with Berg, Berg would have him fired.

In 1984, members of a white supremecist organization came to Denver from Idaho. They shot and killed Berg in the driveway of his home. That year, Berg was being heard throughout the West on Denver's 50,000-watt clear channel station, KOA. His killers felt provoked by Berg's abrasive opinions.

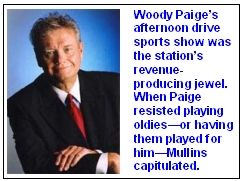

To fill the 2 p.m.–4 p.m. time slot between Berg and a sports show hosted by newspaper columnist Woody Paige, Mullins conducted an on-air appeal for applicants. He envisioned a single host, but Lanie and Myrna, two energetic female homemakers (in that day, "housewives"), applied as a team and impressed Mullins.

Berg soon maneuvered Lanie and Myrna into a time-slot switch. He wanted noon–4 p.m., but Lanie and Myrna didn't want to work 10 a.m–noon. It would interfere with having lunch with their friends. Berg worked it out with Mullins to present the switch as "temporary, just for the ratings period."

At a holiday party at the home of Larry and Devora Deutsch, the pair of hosts repeated that statement. Larry rolled his eyes, and Lanie said, "What!"

Larry asked, "Do you really believe you will get your time slot back if the ratings improve with Berg in it?" The nature of Berg's maneuver sank in, and Lanie and Myrna left the station not long after.

The Deutsch connection: Devora was KWBZ's sales manager; her husband was the sales manager at Channel 9, the station that Mullins' father had owned.

And an aside: When I left KWBZ, Devora said, "Keep in touch." A few months later, I called her to do just that. After exchanging a few words, she asked, "Why did you call?" I replied, "Because you said to keep in touch." She said, "Oh, I didn't mean now." Sometimes, "keep in touch" means "don't keep in touch." I don't always know which. But I do keep in touch with a large number of people I worked with in radio.

I was involved in so many aspects of operating KWBZ, my job was really fun. For example, at one point, Mullins had the idea of playing four rock ‘n’ roll oldies per hour during the talk shows. He hoped the music would catch the attention of new listeners who might be changing stations. Once such a listener stopped to hear the music, he hoped they would continue to listen to the talk segments. I was involved in so many aspects of operating KWBZ, my job was really fun. For example, at one point, Mullins had the idea of playing four rock ‘n’ roll oldies per hour during the talk shows. He hoped the music would catch the attention of new listeners who might be changing stations. Once such a listener stopped to hear the music, he hoped they would continue to listen to the talk segments.

If memory serves, I asked a representative of Broadcast Music Inc., a music licensing company, to come to see me and negotiate a license to play music written by BMI’s member composers. Without such a license, KWBZ would be subject to copyright infringement litigation. Up to that point, as a talk station KWBZ had no music licenses specifically to avoid the expense.

Mullins and I decided not to obtain ASCAP or SESAC music licenses to save at least that expense, so when we went shopping for music, we checked record labels to verify BMI selections.

Many radio stations receive music for free from recording companies. That wouldn’t work for KWBZ, first because there wasn’t time establish those connections, and second because recording companies are less interested in giving away old product compared to product associated with current artists.

Thus, Mullins and I went shopping at Mile-Hi One-Stop, a wholesale supplier to the jukebox trade. Mullins enjoyed picking albums from the shelves, and we left with about $500 worth of records that included I-don’t-know-how-many songs.

Look out. On the air, with no time to train the talk show hosts, here came the oldies. And a bright, bright light shined on one of the difficulties in making changes at a talk station: complaints don’t just come in on the office phone, they go on the air. Most of the callers aired after the change said little about topics the hosts were promoting and a lot about how much they hated the music. Look out. On the air, with no time to train the talk show hosts, here came the oldies. And a bright, bright light shined on one of the difficulties in making changes at a talk station: complaints don’t just come in on the office phone, they go on the air. Most of the callers aired after the change said little about topics the hosts were promoting and a lot about how much they hated the music.

Can you imagine being an advertiser, tuning the station where you bought time, and hearing nothing but listener complaints? The hosts didn’t like the idea, either, and did little to hide their displeasure. Moreover, most of them didn’t know how to introduce or back-announce a song, so they left it to the board operators to play the music as though it were part of the commercial break. “We’ll be back after this break and some music,” Lanie and Myrna would say.

There were exceptions. Boyles had deejay experience from his stint with Bob Lee on the morning show on KLAK; he knew how to introduce a song. “Again, it’s not my decision,” he would tell complainers on the air, and then try to get them on topic. I had fun mixing the music with the talk segments on my show. A weekend host, Johnny Valentine, liked the idea, but he brought his own music: songs from the hit parades of the 1940s. I told him to use the rock ‘n’ roll oldies.

A weekend host who went by the name Damani had the funniest behavior. He let the board operator play the music, but he kept his microphone open and continued talking through entire songs as though they weren’t playing. I told him to stop it, even though I thought it was a clever way for him to protest and sort of comply at the same time.

Paige, the sports show host, put up strong resistance and quickly got Mullins to drop his quota from four songs per hour to two, and then just as quickly to none. The rest of the dayparts soon followed, and the music was gone altogether.

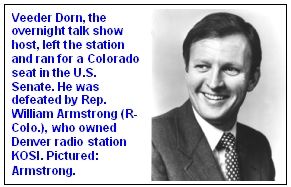

Wait a minute. I didn’t say anything about Veeder Dorn, a talk show host with a Dutch name who fully embraced the music. I mean, fully. When I tuned in to his overnight show, he had converted it from a talk show into an all-music, “all-request” rock ‘n’ roll oldies show. First, that wasn’t the idea. Second, I hadn’t purchased enough music for continous play without a lot of repetition. With Dorn’s impromptu conversion to deejay, the reaction of KWBZ’s independent-minded talk hosts now ranged across the full spectrum from rejection to all-out acceptance. Wait a minute. I didn’t say anything about Veeder Dorn, a talk show host with a Dutch name who fully embraced the music. I mean, fully. When I tuned in to his overnight show, he had converted it from a talk show into an all-music, “all-request” rock ‘n’ roll oldies show. First, that wasn’t the idea. Second, I hadn’t purchased enough music for continous play without a lot of repetition. With Dorn’s impromptu conversion to deejay, the reaction of KWBZ’s independent-minded talk hosts now ranged across the full spectrum from rejection to all-out acceptance.

Footnote: Dorn ran for a U.S. Senate seat from Colorado as a candidate of the then-and-now unknown United States party in 1978. Rep. William Armstrong (R-Colo.), who owned KOSI, won the election.

My time at KWBZ ended when I raised money to buy a part ownership in a Pueblo, Colorado radio station. Who did Mullins hire to replace me? Ron Thompkins, the production wizard I had worked with at KTLK. If Mullins had thought I did some amazing things, I know he had to be thrilled to have Thompkins. I can't think of anyone better.

Ultimately, Mullins' effort to make money with KWBZ failed. The expense of paying high salaries to Boyles, Berg and Paige, along with hourly wages to board operators, contributed to an overhead that the advertising revenue never came close to covering. He discharged all the talk hosts and converted the station to a rock 'n' roll oldies format to save money while he sought a buyer. The station used the records on hand from the talk-and-rock period.

I returned to the station, briefly, after its oldies conversion and after my own ill-fated venture into station ownership. I offered to help Mullins with the hiring, training and scheduling of deejays to cover the broadcast day, and he used my services in that limited role for a while.

I hosted talk shows on several stations. The first was a college station, KCSU-FM. The second was a rock 'n' roll station, KIMN, where the program fufilled part of the station's public affairs commitment. The third was all-talk KWBZ. I've sometimes mused that if I ever were to host a talk show again, I would be ready to use a lot of ideas to stimulate listenership and audience participation that I've accumulated since then.

Jim O’Brien (James Mullica) worked part-time at KTLK during some of the period that I worked there. He had relocated from Florida, he said, because when he heard John Denver’s “Rocky Mountain High,” he just had to come to Colorado.

Mullica had Hollywood-style good looks, and as evidenced by the number of women he attracted. I say “Hollywood,” because he told me one of his dreams was to be an actor. He was a self-promoter and schmoozer, and those are good qualities to have in selling oneself into radio jobs—probably good qualities, generally.

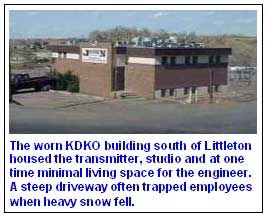

Case in point: David M. Segal had been operating KDKO, a black-oriented radio station, for many years from a combined office, studio and transmitter location south of the Denver suburb of Littleton, Colorado. Segal normally hired black program directors and deejays. Mullica (white, as the Italian name might tell you), convinced Segal to hire him as the program director and morning show host. O’Brien promised increased non-black listenership without alienating the core black audience. Case in point: David M. Segal had been operating KDKO, a black-oriented radio station, for many years from a combined office, studio and transmitter location south of the Denver suburb of Littleton, Colorado. Segal normally hired black program directors and deejays. Mullica (white, as the Italian name might tell you), convinced Segal to hire him as the program director and morning show host. O’Brien promised increased non-black listenership without alienating the core black audience.

O’Brien remembered my work at KTLK and recruited me to host the 7 p.m. –midnight shift. He said Segal couldn’t afford to pay much, so our agreement was that I would work only Monday–Friday, and I would have no commercial production responsibilities. The shorter workweek, less than 40 hours, was intended to offset the fewer dollars. O’Brien also promised me a raise after six months.

Because of my programming background, he also named me assistant program director. I was surprised and pleased when he presented me to the staff as virtually a co-program director. He explained that he and I thought alike about program matters, and asked the staff to follow my requests as though they were his own. We did indeed think much alike, and we collaborated on many of the programming decisions. Because of my programming background, he also named me assistant program director. I was surprised and pleased when he presented me to the staff as virtually a co-program director. He explained that he and I thought alike about program matters, and asked the staff to follow my requests as though they were his own. We did indeed think much alike, and we collaborated on many of the programming decisions.

My program scored No. 1 among teenagers in the next Birch survey. A fledgling audience polling company, Birch didn’t have the respect of Arbitron, but Segal was delighted.

Now, here are some tidbits.

My first day at work, I asked Bobbie, the receptionist, for the station’s public inspection file. My reason was to review the station’s license application to learn what KDKO had promised to air during its current license period—how much public affairs, news, sports and other “non-entertainment” programming. Stations could get in FCC trouble for not performing according to their promises. As assistant PD, I wanted to know, so I could help ensure compliance.

O’Brien later told me that Segal wanted him to fire me for looking at the file. That seems incredible, if it was true. He said Segal was irritated that an employee would look at that information, although the station was required by federal regulation to show it to anyone who asked. I know what could have bothered Segal. The file showed that he owned 60 percent of the station, not the 100 percent he normally led people to believe. I never passed that along, but then again, as public information, it wasn’t a secret, was it?

KDKO’s building and furnishings were in deteriorated condition: loose floor tiles, chipped Formica tabletops, peeling paint.

The swivel chairs on rollers used in the air studio, production room and at the desks used by Bobbie and the business manager, Betty Johnson, would sway from one side to the other, and the rollers would fall off. After my shift one night, without asking, I collected all the chairs and took them to a welding shop for repair. I replaced them temporarily with fiberglass bucket chairs I found in the basement. The swivel chairs on rollers used in the air studio, production room and at the desks used by Bobbie and the business manager, Betty Johnson, would sway from one side to the other, and the rollers would fall off. After my shift one night, without asking, I collected all the chairs and took them to a welding shop for repair. I replaced them temporarily with fiberglass bucket chairs I found in the basement.

O’Brien said Segal wouldn’t pay for the repair, and I would be lucky to keep my job. But Segal told me he was happy someone had finally had the chairs fixed, and praised me for taking the initiative. Let me get this straight: He thought about firing me for looking at the public inspection file (O’Brien said), yet he was pleased that I had fixed the chairs?

My name on the air at KDKO was Tom Steele. Why? O’Brien had ordered jingles to sing the deejays’ names, but the order hadn’t yet come in when I was hired. To avoid the expense of having to buy more jingles one at a time for future hires, he submitted a list of additional names for the singers to record. Subsequent hires had to select names from that list to correspond with the anticipated jingles.

When the jingles came in, they were terrible, and they never were used. Instead, I used special effects to record my voice in a low register to announce the deejays’ names and other station promotions. In that way, I became the station’s image voice.

My time at KDKO came to an end when I noticed that my first paycheck after six months did not include the raise that O’Brien had promised. I spoke to him about it, and he said that the raise had been contingent on a ratings increase, and the Arbitron ratings hadn’t increased. I said there had been no such contingency, and I wanted the raise.

About that time, O’Brien said he wanted to take himself off of the morning shift. He assigned me to take his place and hired another deejay for 7 p.m.–midnight. During my first week hosting the morning show, O’Brien said Segal told him that he wanted him back on the morning show. On Friday, O’Brien came into the studio and told me that Segal wanted to see me. I visited Segal in his office, where he terminated me.

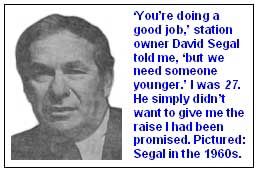

“You’re doing a good job,” he said, “but we need someone younger.” I was 27. That reason didn’t make sense, but terminated is terminated. What I think happened is that O’Brien never told Segal when he hired me that he had promised me a raise. When I called him on it, he couldn’t deliver. He had to find a way to move me out, and thus the shift changes that disguised his real intention behind hiring a new 7 p.m. –midnight deejay. “You’re doing a good job,” he said, “but we need someone younger.” I was 27. That reason didn’t make sense, but terminated is terminated. What I think happened is that O’Brien never told Segal when he hired me that he had promised me a raise. When I called him on it, he couldn’t deliver. He had to find a way to move me out, and thus the shift changes that disguised his real intention behind hiring a new 7 p.m. –midnight deejay.

I didn’t have any hard feelings about it, though. Such was the revolving door that was radio deejay work. Thanks to help from Paul Pettit, who performed engineering services at both KDKO and KWBZ, I was soon hired at KWBZ. I continued providing voice imaging for Segal for a while, and O’Brien and I later went into business together. He also helped me to get hired at KTLK.

Postscript:

A year after I had left KDKO, Segal sold the station to Sterling Recreation Organization, and Rod Louden became general manager. O’Brien had left to take a job selling shipping supplies (which led him to start a successful supply business of his own). Louden called me at KWBZ where I was by that time the operations director, and he asked me to lunch.

At lunch, where Louden was served a barely cooked hamburger that he sent back to the kitchen two or three times before giving up on it, he said that he wanted to hire me for the morning show. We agreed on the responsibilities and a salary, and he hired me on the spot.

He told me to visit the station one evening to meet the program director, “Damien,” who worked the 7 p.m.–midnight shift. I made an appointment and came to the station. Damien asked me whether I had brought an audition tape. No, I hadn’t. He asked whether I could record one in the production room. I said I probably could, but I noticed the production room had no headphones.

“Didn’t you bring headphones?” Damien asked.

“No, I don’t own any headphones,” I said.

“Can you bring headphones from where you work now?” he asked.

“There aren’t any headphones where I work now,” I said.

“How do you record commercials?” he asked.

“I record my voice for playback and mix it with music and jingles while listening on speakers,” I said.

That was one peculiar meeting.

I called Louden the next day and told him it didn’t seem to me he had told Damien that I had been hired. Louden said that he had a problem to work out, and not to worry. He would get back to me. He never did.

Something must have made me cautious about Louden’s hiring me during that lunch, though, because I didn’t immediately give notice at KWBZ. After that phone call with Louden, I simply continued in my operations director job with the talk station. I often cite this incident as "the shortest job I ever had in radio": Hired for the morning show, but never given a date to start work.

Home www.donbishop.net

|